A unified theory of the death of partying

and why I no longer support the Party Throwers' Tax Credit

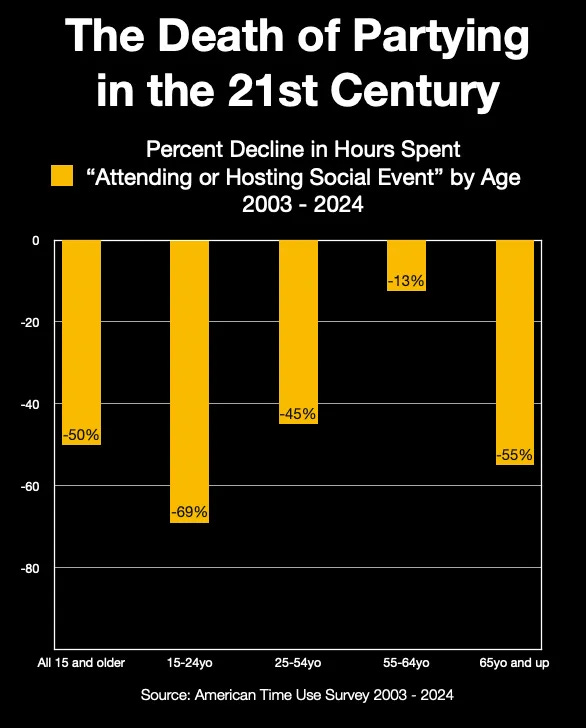

A couple of months ago Derek Thompson published a widely circulated post about partying in the USA, which according to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) has dropped precipitously in the past twenty years, especially among young people. You have maybe seen this chart:

By now most people have forgotten about death-of-partying-discourse and moved on to the next big dread-inspiring social trend (“bed rotting”?). Not me. After reading Derek’s post, I became a little obsessed with the death of partying and how it might best be counteracted; on Twitter, I half-jokingly proposed a “party throwers’ tax credit”. But that was just the beginning. Upon obsessing further, I started to wonder if a tax credit was the optimal solution. Was the decline of partying really a supply-side problem? If it wasn’t, a party throwers tax credit wouldn’t be the appropriate response. Then I began to wonder if the decline of parties was a problem at all. If the goal was not necessarily to increase parties per se, but to maximize social cohesion and aggregate well-being, wasn’t I being a little too technocratic in my insistence on partying as “the one best way” to achieve this?

The crank armchair economist in me was aroused. Over the next few months I spent way too much time attempting to arrive a model of party provision and to identify shocks that might explain its decline. What follows are my “findings” — maybe not QJE-grade, but good enough for Substack.

Partying is a gift economy

Just now I hinted at my attempts to shoehorn partying into the classic supply-demand model. But after chewing it over a little more I decided I was barking up the wrong tree, for the obvious reason that parties - and here I’m thinking of privately hosted social gatherings, not ticketed events - are not a market good1. E.g. By my own definition, parties (or to be a little more precise about what we’re discussing here, party slots) are not bought and sold.

Non market goods are famously cumbersome and annoying to provide. Society has different ways of providing them, depending on the the type of non-market good. Public goods like parks, national defense and so on are provided via taxation. Parties, it seems clear to me, are provided via a gift economy. Here is the definition of a gift economy from Wikipedia:

A gift economy or gift culture is a system of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture; although there is some expectation of reciprocity, gifts are not given in an explicit exchange of goods or services for money, or some other good or service. This contrasts with a market economy or bartering, where goods and services are primarily explicitly exchanged for value received.

I think the application of this model to partying is pretty intuitive. No one is demanding compensation at the door when you attend their party, but it’s also a little gauche to not reciprocate somehow; even drunk 22-year-olds recognize the stigma of “showing up empty handed.” There is, moreover, a mild expectation that invitees will at some point in the future throw a party of their own, to which they will invite the host.

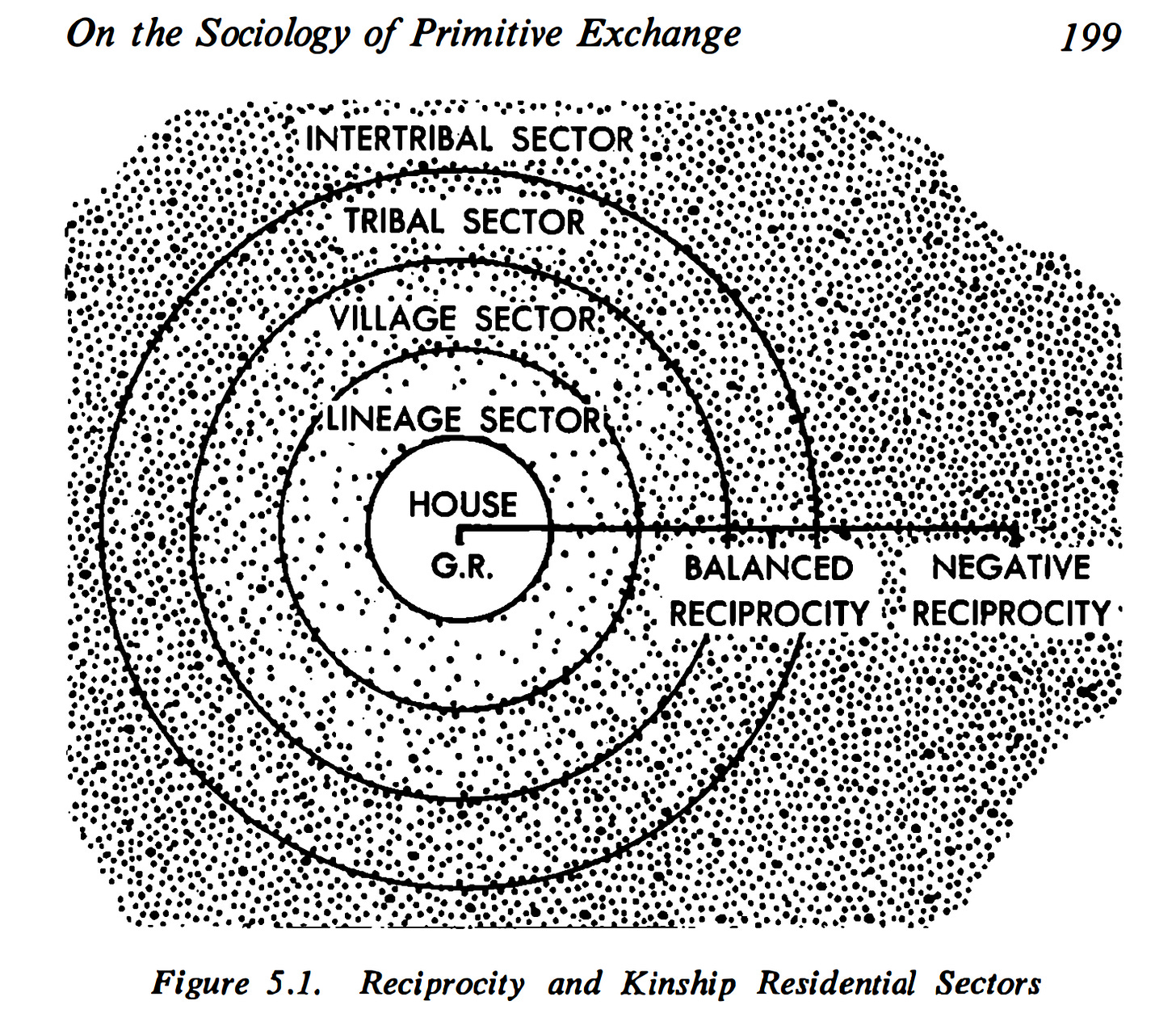

What keeps a gift economy going? Why might a gift economy fall apart? That may depend on exactly the type of gift economy we’re talking about. In Stone Age Economics (1972), the cultural anthropologist Marshall Sahlins proposed a spectrum of reciprocities ranging from “generalized” reciprocity, in which the return period is indefinite and debts barely accounted; to “balanced” reciprocity at the midpoint, in which contributions are tracked and expected to balance out within a definite timespan; to “negative” reciprocity, in which “the participants confront each other as opposed interests, each looking to maximize utility at the other’s expense” (which sounds a lot like…..the market?).

A critical feature of this scheme was the proportional relationship between expected reciprocity and social distance:

I think Sahlins’ diagram above is quite suggestive as to a factor behind the decline of parties. Something Derek and other people who cover the loneliness epidemic talk about a lot is the decline in middle-ring ties - relationships with people who are somewhere between family/best friend status and “guy online who likes the same sports team as me.” Middle-ring ties might be neighbors, people from PTA, from church, or any number of voluntary associations.

A robust middle ring is needed to sustain a non-market party economy. You have to know more people than just your best friend and your family in order to throw a party; but in order to prevent free-riding — which most of us are pretty averse to — those people need to be close enough that reciprocity can be tracked. Otherwise, as Sahlins warns, everyone defects and the party economy falls apart: “Equivalence becomes compulsory in proportion to kinship distance lest relations break off entirely; for [my emphasis] with distance there can be little tolerance of gain and loss even as there is little inclination to extend oneself.”

A particularly dramatic illustration of the reciprocity tracking principle when it comes to partying is East Asian red envelope culture. When you’re invited to a wedding in China (or Japan, Korea, Singapore etc), you do not go to the couple’s registry to find which blender or dish set they would like; you simply present them with cash in a red envelope (hongbao). The couples’ parents will often record the amounts given by each person (sometimes, literally, in a ledger) so they can know how much to give in the future, a practice referenced by a Ms. Wang in a recent NYT article on hongbao culture:

Ms. Wang said her mother’s principle was always: “You have to remember how much the person gave you, and you reciprocate, but never the equal amount of value. It shouldn’t feel like a market transaction. Reciprocate by adding a little more to indicate you want to continue to have a relationship with that person.”

I attended numerous weddings over the years I lived in China but I was never, it was made clear to me, expected to present the couple with a hongbao. I have to imagine this was because I was an outsider and people understood my stay in the country was temporary. My Chinese hosts, in other words, did not consider me part of the “village,” so it made more sense to just let me free ride.

Not such a big deal, financially, when it’s just one person you’re letting freeride - but what happens if a larger share of potential invitees are people you might not see again? If these potential guests understand you might not attend their kid’s wedding - say, it’s taking place in a foreign country - they’re probably not going to present you with a fat hongbao. If you’re not going to get a fat hongbao that helps you recoup the cost of that person’s wedding meal, you might just not invite them….and so on. Everyone defects and the game falls apart! Ms. Wang gestures at exactly this problem toward the end of the article:

“If we lived in a perfectly closed community, everybody would know their positions and they would know how much to give, but the reality is that we’re always mobile,” she said.

Here Ms. Wang helpfully posits a contrast between the “perfectly closed community” on one hand and a hypermobile population on the other. China has famously transformed, in the past several decades, from a place where most people never left their ancestral farming communities to one where nearly 70% of the population lives in cities. This astonishing phenomenon has had a lot of effects which are outside the scope of this article but one is that it presumably makes it a lot harder for reciprocity to be tracked. I would be surprised if hongbao culture doesn’t start declining in China over the next few decades.

It’s tempting to blame the collapse of partying and middle-ring social networks on increased mobility. But the relationship is far from straightforward. For one, and contrary to most people’s intuition (certainly mine), Americans are less mobile than they used to be, with interstate mobility peaking in 1990 - even among young college graduates. And it’s also not clear that increased mobility can explain the fraying of social networks: A tidbit that really jumped out at me from Yoni Applebaum’s Stuck is that as of the mid-century, membership in voluntary associations was actually higher among Americans who had moved cities.

So mobility alone cannot explain the decline of the middle ring, and thus partying - for that we will have to turn to some other factors.

Party throwing costs have increased

Suppose:

expected payoff of throwing party = expected benefit of throwing party - cost of throwing party.

So far we’ve discussed how the collapse of intermediate or middle-ring social networks has eroded the expected reciprocity benefit of throwing parties. But the fact that payoff is net of cost suggests further, if complementary, explanations for the decline of partying.

Over the past few decades, thanks to the advent of globalization and industrial agriculture, the real cost of most party inputs like beer, paper plates and baby carrots has fallen. The one input that has not fallen in cost is time. And this has become really, really expensive. As anyone who follows fertility crisis discourse knows, economists believe the opportunity cost of time has skyrocketed for two main reasons: 1) women being allowed to enter the workforce and 2) the widespread availability of cheap, potent entertainment like streaming, scrolling and video games.

We can see how this increase in the cost of time might directly impact party provision, especially given that women have historically been the ones given to social organization.

Consider for example the social life of my maternal grandmother, who was a housewife in Elgin, Illinois. She hosted often, having over neighborhood families for dinner and women from Hadassah for bridge. My mom, who worked full time (as an economist, incidentally; she consulted on this post), hosted some when I was a kid but not nearly as much as her mother. It’s easy to see why. The opportunity cost of my grandmother’s time was a lot lower. My grandmother didn’t work and on the occasions she made forays into the workforce it was as a substitute teacher, which is not super lucrative. Nor did my grandmother have access to super abundant entertainment. Video games and streaming were not a thing. There were like three channels on TV. Mostly for entertainment she gossiped with her friends on the phone.

As Derek (somewhat sheepishly) notes in his post, the entrance of women into the workforce has been pretty bad for party provision. In fact, I think it’s been bad for the provision of a lot of other non-market social goods. Take neighborhood vitality. If you read Jane Jacobs’ Death and Life of Great American Cities, you’ll find a great deal of the first few chapters is devoted to the role of housewives in maintaining the quality of public space - using city parks during the day while everyone else is working; keeping “eyes on the street”; etc.2

I want to venture that the overall increase in the opportunity cost of time has had another, more subtle, effect on the calculation above. Suppose the cost of peoples’ time goes up: this implies that not only party hosting but party attendance becomes more costly and all else equal, invitees are more likely to decline or no-show a given invite. Party hosts understand this elevated risk, which adds further cost to hosting in the form of anxiety about rejection, e.g. what if no one shows up?

There is a passage from White Noise I think about all the time that’s an absolutely perfect illustration of this effect, in which Murray, the pervert-with-a-heart-of-gold Elvis Studies professor, invites Jack Gladney and his wife Babette to dinner:

Before Murray went to the express line he invited us to dinner, a week from Saturday.

“You don’t have to let me know till the last minute.”

“We’ll be there,” Babette said.

“I’m not preparing anything major, so just call beforehand and tell me if something else came up. You don’t even have to call. If you don’t show up, I’ll know that something came up and you couldn’t let me know.”

“Murray, we’ll be there.”

“Bring the kids.”

“No.”

“But if you decide to bring them, no problem. I don’t want you to feel like I’m holding you to something. Don’t feel you’ve made an ironclad commitment. You’ll show up or you won’t. I have to eat anyway, so there’s no major catastrophe if something comes up and you have to cancel. I just want you to know I’ll be there if you decide to drop by, with or without kids. We have till next May or June to do this thing so there’s no special mystique about a week from Saturday.”

White Noise was written in the 80s and if you ask me — the former host of a cult favorite slacker literary podcast — it’s about how TV is re-wiring our brains. Maybe one of the ways TV started deforming our psyche was in decreasing our expected payoff from socializing.

Another factor Murray gestures at in this passage is the role of children in adult socializing. Obviously, having young children who need care raises the cost of both party attendance and hosting - but that’s always been true (and really it should be less of a factor because people have fewer children today than they used to). I suspect what has changed in the past few decades, and what might help account the decline in partying, are social norms around how closely children should be supervised, and whether it’s appropriate to bring them to grownup social events. If kids need to be watched at all times and are also not welcome at grownup social events, that’s going have a chilling effect on partying!

The flip side of this is that cultures that have more chill norms around kids will probably see more partying. I remember once talking to an Iranian-Canadian woman who told me that when she was a kid and her Persian relatives wanted to get together with their friends to hang out, they would just throw the kids in the basement and then party until the early hours of the morning!

Parties have lost some of their horny value

So far I’ve discussed the decline of partying in terms of middle american families with children. But according to the ATUS, the most precipitous drop-off in partying has been among young people. Why might this be the case? One obvious explanation is that today’s young people are digital natives and highly immersed in social media, streaming and video games. The opportunity cost of their time is much, much higher than that of their counterparts twenty years ago.

I don’t doubt this factor holds some or even a lot of explanatory power. But I want to focus a little on another trait unique to the younger demographic, and that is that they are more likely to be single.

Since at least Jane Austen times, parties have served as matching markets. Indeed, there used to exist a whole subgenre of party — the debutante ball — whose explicit purpose was the matching of young ladies with prospective husbands. And here I’ve created for myself the opportunity to quote from what is to my mind one of the greatest character sketches in all of literature, that of the socialite Archie Gilbert in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time3:

His whole life seemed so irrevocably concentrated on ‘débutante dances’ that it was impossible to imagine Archie Gilbert finding any tolerable existence outside a tail-coat. I could never remember attending any London dance that could possibly be considered to fall within the category named, at which he had not also been present for at least a few minutes; and, if two or three balls were held on the same evening, it always turned out that he had managed to look in at each one of them. During the day he was said to ‘do something in the City’—the phrase ‘non-ferrous metals’ had once been hesitantly mentioned in my presence as applicable, in some probably remote manner, to his daily employment. He himself never referred to any such subordination, and I used sometimes to wonder whether this putative job was not, in reality, a polite fiction, invented on his own part out of genuine modesty, of which I am sure he possessed a great deal, in order to make himself appear a less remarkable person than in truth he was: even a kind of superhuman ordinariness being undesirable, perhaps, for true perfection in this rôle of absolute normality which he had chosen to play with such éclat. He was unthinkable in everyday clothes; and he must, in any case, have required that rest and sleep during the hours of light which his nocturnal duties could rarely, if ever, have allowed him. He seemed to prefer no one woman—débutante or chaperone—to another; and, although not indulging in much conversation, as such, he always gave the impression of being at ease with, or without, words; and of having danced at least once with every one of the three or four hundred girls who constituted, in the last resort, the final cause, and only possible justification, of that social organism.

For various reasons, the days of this particular social organism are now over. There is probably a whole substack or even dissertation to be devoted to that organism’s decline, and another to the transfer of spouse search costs from the parents and friends of single people to the single people themselves. What has not changed since the days of deb balls is that single people attend social events with either the express intention or coolly concealed hope of “meeting someone.” Scott Alexander, who met his wife at a party, has conceptualized this strategy neatly as “accumulating micromarriages.”

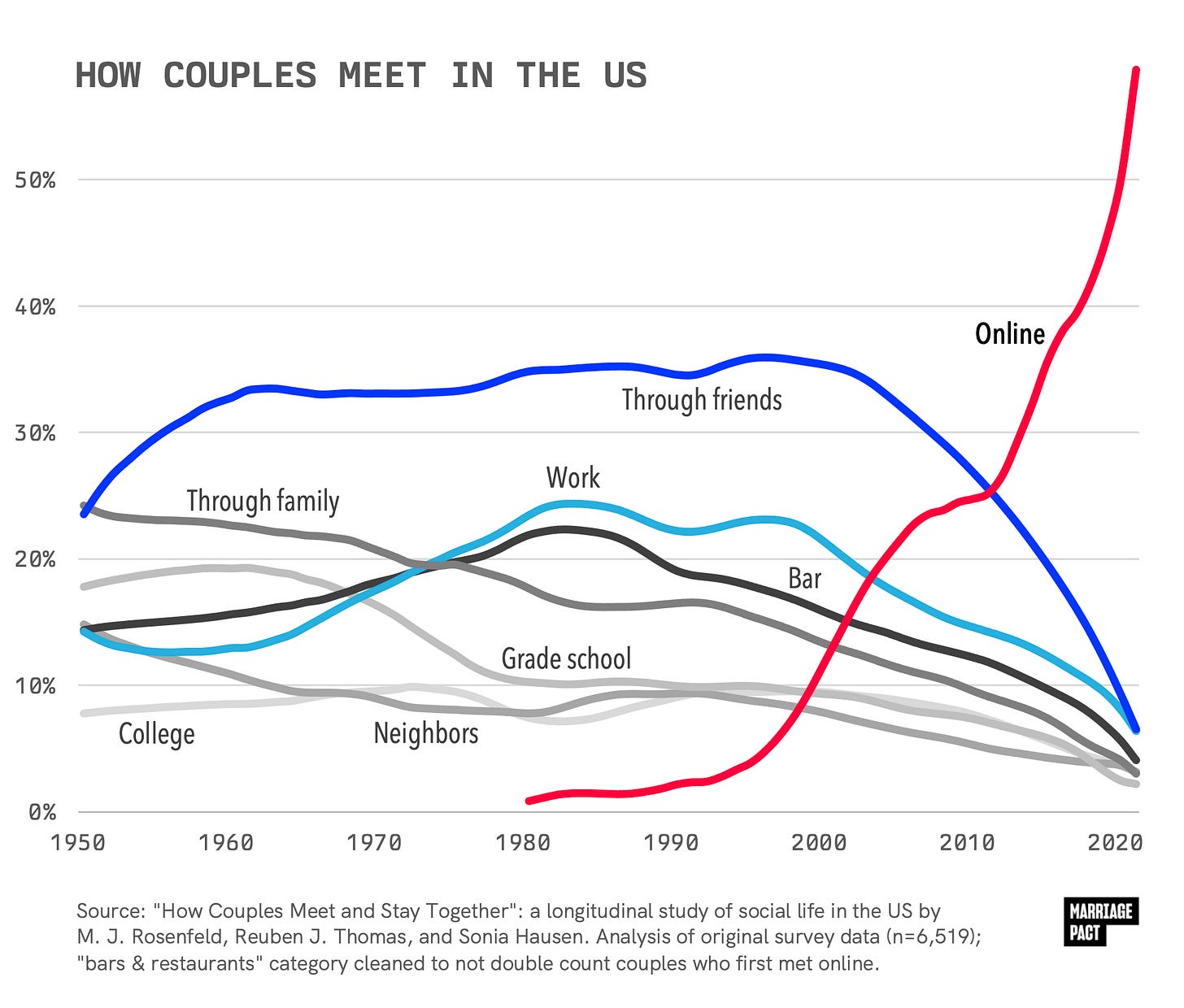

A technological innovation you’re probably aware of has disrupted partying’s monopoly on micromarriage provision. Over the past twenty years, the share of couples meeting on dating apps has skyrocketed, while the share meeting through all other modes has declined:

Dating apps being responsible for the drop-off in partying among young people has been a live theory for at least a decade. But up until I arrived at my theory about reciprocity and payoffs I was never quite satisfied with it. Thinking about it from the demand side, wouldn’t we expect the singleton seeking to maximize his/her/their chance of meeting a mate to see dating apps as a supplement, not a substitute, to partying?

The theory makes more sense if you think of partying in terms of host-side payoffs. Recall that future expected payoff = future expected benefit - cost. If the expected benefit comes in the form of reciprocity (invitation to future parties), that benefit has less value as soon as there is a (practically costless) alternate method of meeting mates. And this slightly reduced benefit might not be enough to outweigh the costs of hosting, which as we’ve established have become considerable.4

Another development that has reduced the value of expected reciprocity benefit is the emergence of professionally organized social opportunities - namely, team sports, which have become hugely popular in recent years. According to a CivicScience survey, the share of U.S. adults participating in team sports has doubled since 2020, from 11% that year to 20% this year. This makes a ton of sense to me: people are totally exhausted by dating apps and sports are known to be a fun (and healthy!) alternate way of “meeting someone,” to the extent the horniness of run clubs in particular has become a bit of meme:

I also don’t think it’s a coincidence this trend emerged in the aftermath of COVID - the pandemic famously made everyone but especially young people more risk averse, which of course raises the cost of party throwing. A VOLO sports membership (including “endless experiential programming” and “curated social experiences”), meanwhile, costs only $35/month – which I suspect for a lot of single and friend-seeking young people is a much better value prop than the delicate venture of party hosting.

Will professionally organized socializing ever outcompete privately hosted partying completely? I think it’s very unlikely. The reason for this is what my mother somewhat uncharitably calls “the lemons problem”: when the only barrier to entry is a nominal fee, anyone - simply anyone! - can join, which increases the proportion of “undesirable” people. I mean undesirable in the nonmoral sense here - not bad or unattractive people, just people who are not exactly what you’re looking for. And of course a preponderance of lemons makes searching less efficient.5 Theoretically, private party hosts will always be much better than the market at the curation and gatekeeping of people. (Not that the market hasn’t tried - there’s a dating startup in SF called frnds of frnds [“modern dating, the old fashioned way”] that more or less seeks to simulate the curation & gatekeeping effects of private parties. We’ll see how that goes!)

Sometimes people party for clout

I’ve harped a lot on payoffs and how various shocks have altered the tit-for-tat calculus of party throwing in a way that might explain the observed society-wide decline in party attendance and hosting. But there are pockets of society in which partying is alive and well - namely, the rarefied circles of the uberrich.

I argue the continued existence of partying in such circles is the exception that proves the rule. For one: party hosting costs to rich people are always lower because money is worth less to them. The time consuming aspects of party preparation can be easily outsourced - there is a whole industry devoted to this.

More importantly, though – and I’m just going to assert this – the expected benefit of party hosting for rich people takes a different form. Status, not reciprocity, is the primary expected benefit for such partiers. And since status is rivalrous, clout-seeking hosts are constantly in competition with one another. Each “round” of the game generates further and more grandiose parties.

Theoretically, the game in which party hosts expect payoff in the form of reciprocity should generate just about the number of parties desired by the community as a whole. But when players are competing for status, increasingly untethered from actual demand, no such equilibrium is guaranteed. Indeed, such circles are likely to see an oversupply of parties, the tediousness of which has been exploited to comic effect in the work of satirists like Armistead Maupin, Anthony Trollope, Jane Austen, Edith Wharton and me if I ever write my roman à clef about my time in the New York literary scene.

An interesting implication of partying for status is that clout-conscious party hosts will tolerate a much a higher level of free riding, because reciprocity is not as important to them. For a demonstration of this we need look no further than the social life of my paternal grandfather, who was for decades press officer at the Portuguese embassy in Washington. Through that gig he met lots of rich people and attended, over the course of his life, hundreds of cocktail receptions, dinner parties, balls and so on.6 Yet my dad claims my grandfather did not host even once. So why did people keep inviting him to their functions? The answer is simple: My grandfather was very handsome and charming; he enriched the party experience with his mere presence. In this sense, I suppose, my grandfather was not free-riding at all but in a Pareto-optimal arrangement with status-conscious party hosts.

I guess the lesson here is that if you want to get invited to a lot of parties but never do the work of hosting, you should become very attractive, interesting or famous - or even just extraordinarily palatable like Archie Gilbert.

Conclusions and recommendations

Is partying completely toast? I don’t think so. In this piece I’ve identified a host of factors that might be responsible for the decline of parties. Some are pretty intractable, while others can be addressed with policy and markets.

One of the more intractable factors is the collapse of extremely tight and highly surveilled gift networks that all but guaranteed the provision of parties by allowing reciprocity to be tracked (“balanced reciprocity”). I do not foresee such community structures returning to the Western world. And frankly, it would be sentimental and unreasonable to hope for such a return. There’s a reason people left their small towns and tightly knit communities - they were stifling!7 Closely related to the decline of such networks is the entrance of women into the workforce. This is another trend I do not think is likely to be reversed although who knows.

Something markets can actually help with is reducing organizing costs. Anyone who attends social events in New York or SF is likely familiar with a product called Partiful. This nice little software makes it extremely easy to invite a bunch of people very quickly to your party, track RSVPs and sends out little text blasts to boot. While I was writing this I received a Partiful invitation from my friend Ivan to an event called “the party to forge bonds.”8 The gist of the event is you should invite 2-3 people you’ve talked to like one time but would like to know better. Before Partiful, searching out these glancing connections would have been difficult and frankly a little weird — but now you can just go to the Partifuls of past events you’ve attended, boop the invite button on that person’s name and invite them! They won’t even think it’s that weird because it required so little effort!

Partiful can also help get around the scale problem. Recall that once a party reaches a certain size, it is hard for the expected reciprocity benefit to outweigh the costs of hosting because there are simply too many people for reciprocity to be tracked. With Partiful, you can socialize the up-front costs by adding a suggested donation which can be paid through integration with Venmo. I’ve never thrown a party big or ambitious enough where it’s been necessary to do this but I have happily contributed to large format events thrown by the superstar hosts up at Avalon, who regularly open up their incredibly sick group house at the top of Twin Peaks for esoteric gatherings such as last week’s “Hildegard Festival,” which I’m told featured roast duck, stewed rabbit, pottage and other delicacies (as well a choral performance and lectures on the life of Saint Hildegard) in exchange for a $20 suggested donation. Not bad!

Do I still support the Party Thrower’s Tax Credit? Not really. While I personally would love to get money from the government to throw parties, the think tank guy in me can’t help but long for technology-neutral solutions. I think we have to think about what we’re solving for here. If what we really want is to encourage social cohesion and well-being, maybe what the market has shown is that team sports, not partying, are people’s preferred vehicle for social connection — in which case, maybe the death of partying does not warrant a policy intervention at all!

Yet something, if the last few weeks have been an indicator, warrants an intervention. Americans are clearly lonely, angry and divided. I think what we really want is for people to interact more IRL and experience community. And when it comes to this, I’m a big fan of a technology neutral intervention like a Pigouvian attention tax. The idea here is that big tech companies are currently not internalizing the serious negative externalities of their products and should be made to do so. An attention tax would lower the opportunity cost of people’s time by making scrolling, streaming and video games more expensive - which would perhaps tip the calculus in favor of more pro-social, IRL activities like team sports, churchgoing or even, yes, partying.

A final thought: you should throw a party. Yes, you! They do not require as much effort as you think they do. I know this because, as those of you who read the footnotes know, I am a frequent party thrower. Remember: the value-add of your party is not your beautifully appointed home or exquisite spread of snacks. The market can provide these things. Your value add is in your ability to curate and bring together people. Unless you really suck at curating people - and admittedly, some people are better at it than others - everything else is trivial.

If you’re still hesitant, perhaps you’d like to know my braindead recipe for throwing successful parties. It is time tested! Here it is:

invite 30-40 people on Partiful without thinking too much about it

ask ChatGPT to make me a batch cocktail recipe using whatever liquor I have on hand

Make some dill dip and put out it out with some baby carrots

that’s it

Now go and put something on the calendar — it’s your patriotic duty!

Why parties have never fully become a market good — unlike food, water, housing and pretty much everything else — I will get to later on.

Does this mean the entrance of women into the workforce is bad on net? Of course not. But it’s silly to pretend that it hasn’t had a cost to society.

That Archie Gilbert is probably only the 35th most important character in Dance and still warrants such a magisterial introduction really speaks to the unique pleasures of that work, which, to be clear, I am still only 15% of the way through (it is twelve volumes long)

Personally, I would rather slice off one of my own fingers than spend another minute on a dating app, which might explain why I host a higher-than-average number parties. Also: my hosting costs are lower than average because, for all of my other neuroses, I am freakishly immune to social anxiety. For whatever reason I am constitutionally incapable of caring more than a little bit about what people think of me, my apartment, etc.

To furnish some further anecdata from my life: Take as an example my membership in the Golden Gate Triathlon Club, which I joined after in a fit of grandiosity I registered for a triathlon and then realized I needed to figure out how to actually train for one. I like all my fellow members of GGTC, but I don’t have much in common with the modal member beyond a borderline psychotic commitment to endurance sport — I don’t, in other words, expect to meet my future boyfriend or bestie there. If I had to bet on it, I would say I am much more likely to meet such a person at a party hosted by one of my cool, highly networked SF friends like Rachel or Jasmine, where I have historically had a lot more in common with the average guest.

although not my bat mitzvah, in lieu of which he famously sent me a framed copy of this photograph of himself.

for a chilling literary illustration of this point as well as the deleterious social effects of monopsony labor markets look no further than Larry McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show.

a bit of a ripoff of my “party to cure social ills” circa July but whatever….imitation is the highest form of flattery….

I wonder how much the housing market is an influence here, too? Not so much because people lack space, but because they have roommates—and it seems harder to get 2-4 people to agree to a time and a guest list than for one person (or a couple, where it’s more normalized to say “this is what we’re doing Saturday night”) to decide to host. My roommates are dear friends but even so I think I host less living with them than I would living alone! Designated group party house collectives are a different story, of course. But those are a lot less common.

Your mom's lemon theory sounds like she's referring to a market for lemons. That is, the worst people (most annoying, least enjoyable to hang out with, etc) are most often looking for parties or friends, since they quickly stop receiving invites. See also: Dan Luu's wonderful essay on the subject.